Vulnerability Research and the Importance of Supporting Young Talent

By: Matt Harrigan

Warning: Old security curmudgeon narrative incoming!

I’ve been working in the cybersecurity space since before there was an industry wrapped around it – the pre-firewall, “maybe TCP wrappers are good enough, ok ouch, maybe not” days. One observation I’ve had multiple times is that we tend to forget which ideas have propelled us forward, and which have held us back. Specifically, we tend to selectively remember that this industry was born entirely of hackers, doing hacker things, exploring undocumented technology, fiddling, tinkering, breaking, and fixing.

In 1994, when I was 20 years old, I started one of the first companies to offer security assessment and penetration testing services to corporations. I knew absolutely nothing about business, but I was convinced that I could help. Timing-wise, it couldn’t have been better – internet adoption was growing very quickly, and people were trying to find new use cases for it. Cyber-attacks were largely not covered in traditional media, because the stakes were relatively low – not all data was digital, and not all things were connected, but early adopting companies knew what was coming.

Back then, IRC (Internet Relay Chat) was where you talked to other people who had an acute interest in infosec, and if you were brave enough, you would meet up with these people at cons like DEF CON or PumpCon (which at the time had -maybe- 100 people in attendance). In my opinion, a huge contributing factor to the success of this industry is that open conversation and collaboration on weird, cool, and scary security projects wasn’t even “encouraged,” it was just how we did things. In other words, open disclosure about vulnerabilities in a tight-knit community was very normal. A very specific memory I have of this is Mudge disclosing that Kerberos 5 had a race condition at a very early PumpCon, and a roomful of hackers scampering off to go try new and fun authentication games.

Since then, things have changed dramatically. There are behemoth-level companies in this space that rake in billions and billions of dollars in revenue annually, and millions of people work in the cybersecurity industry. Companies are bigger and what we do is table stakes.

Unfortunately, because there are so many moving parts, sometimes we lose our way and improper disclosure happens. I was in fact personally guilty of improper disclosure at least a few times in the early years of the internet. There have been a multitude of incidents over the last 15 years or so involving feuds between vendor organizations and security researchers about the methods and timing of vulnerability disclosure, and the particulars of individual vulnerabilities. Emotions sometimes run high in infosec because this work isn’t easy and often, the intent of one party is misunderstood by another. There are many notable examples of this, which I am not going to detail, but suffice to say, it does sometimes feel like people have forgotten that security research started with hackers trading 0-days over DCC.

One of my favorite things about this industry is meeting people who are relatively new to it and seeing how they address some of the sociology that I described earlier. So, when I saw Brian Krebs’ article on the work performed by a young man named Logan George with respect to Juniper’s support portal, I reached out to Logan directly.

Unlike the early 90s, there are now established processes, personnel, and procedures that make the disclosure of vulnerabilities safe and healthy for both technology product manufacturers and researchers. That said, I was immediately impressed by Logan – he had reached out to Juniper’s JTAC and gotten clearance to discuss this issue publicly. He was clear and concise in his description of the issue, and he followed all the appropriate channels. Soon thereafter, we set up a call to get to know one another and talk about where he wanted to go with this.

Logan expressed the desire to release a more comprehensive report on the issues he discovered, and given Leviathan’s 18-year history of generating reports that identify and describe cybersecurity issues, it became clear that it was incumbent on us to help Logan articulate his findings in a manner that is understood by others in the security community. For the next few weeks, we worked together on a report that met this criteria and made sure to work through all the appropriate channels at Juniper. To be clear – everything you will read is Logan’s work, and all we’ve really done here is provide guidance and review.

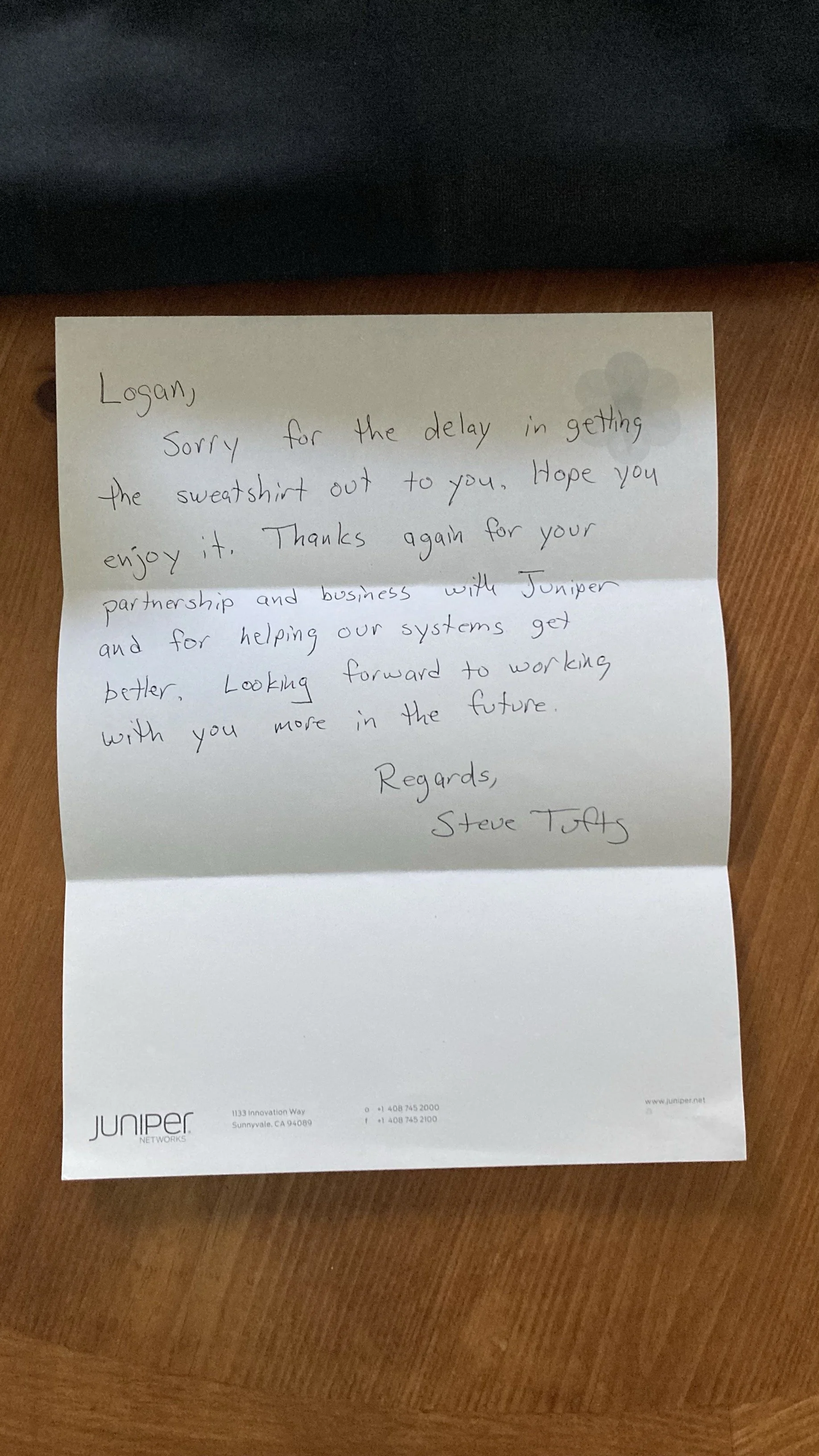

Logan’s work was also reviewed and approved by the kind folks at Juniper Networks, who were gracious enough to send him some corporate goodies, and provided some supporting context:

“We at Juniper take our position as a telecommunications supplier very seriously and work hard to reduce and remove vulnerabilities in our products. Insights from independent researchers are a key tool to bring different perspectives to our efforts, and we value their input. When following responsible disclosure practices, the significance of their contribution is only amplified.“

- Drew Simonis, CISO Juniper Networks

All that said, this is a story with a happy ending where we were able to get back to the collaboration from the early open disclosure days, utilize modern practices to ensure responsible handling of the information, and allow a young person to make a positive contribution to infosec. It’s a win-win-win. That said, without further ado – here is a link to Logan’s findings. After you’ve read it, please take a moment to connect with him on LinkedIn and extend a warm welcome to him from the larger infosec community.